Creating Space for the Sacred Snow Leopard

Creating Space for the Sacred Snow Leopard

Blog Article Written by Darla Hillard

The Conservancy extends grateful thanks to Almagul Osmanova and Kuluipa Akmatota for their excellent logistics planning for our recent Land of the Snow Leopard Network gathering in the spectacular Tien Shan Mountains of Kyrgyzstan. Thirty participants convened, from the Altai and Buryat Republics of Russia, from Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, and the US.

While we hope our Network will grow to include the Himalayan regions, for now the focus is Central Asia, where snow leopard habitat includes the Pamir, Tien Shan, Altai, and Sayan Mountains. Many Indigenous communities who share these highlands uniquely honor Snow Leopard as a spiritual protector, and as a unifier of humanity.

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan has been an independent republic since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. At the center of its richly complex history is a thousand-year-old epic poem recounting the life story of Manas, a towering figure who fought to establish and defend a homeland for the Kyrgyz people and free them from oppression. The poem, said to be 30 times longer than the Odyssey, has been passed down orally through the centuries, through chanters known as Manaschis. Scholars call the poem as stirring as ”The Iliad,” as episodic as ”Don Quixote,” and as rich in moral guidance as the Gospels.

During our workshop we had the treat of a morning spent at the historical park dedicated to this hero. A mural near the end-point of the museum displays shows the aftermath of Manas’s death in China and his widow, Kanikey, bringing their son back to safety in Kyrgyzstan. There’s a sword at the bottom of the painting that we were told has been passed down from one master-chanter to another. When I asked who has it now, our interpreter, Kyialbek, clarified, “the sword is the poem.”

During our workshop we had the treat of a morning spent at the historical park dedicated to this hero. A mural near the end-point of the museum displays shows the aftermath of Manas’s death in China and his widow, Kanikey, bringing their son back to safety in Kyrgyzstan. There’s a sword at the bottom of the painting that we were told has been passed down from one master-chanter to another. When I asked who has it now, our interpreter, Kyialbek, clarified, “the sword is the poem.”

Today some six million people live in Kyrgyzstan, which has about the same land area as Nebraska.

Our Journey to the Talas River Valley

From Bishkek we rode northwest for eight hours in two comfortable buses, over two high passes, to reach our workshop venue in the beautiful Talas Valley.

Between the two passes, we had a long break at the summer camp of a herder family.

They fed us an amazing lunch of traditional foods and showed us how kumis is made—the traditional drink of fermented mare’s milk that is a household stable in Kyrgyzstan and elsewhere in Central Asia. It tastes a little like sour yogurt.

This family is part of a pastoralist herders’ network that has been engaged by Rural Development Fund, one of the Collaborative Partners, (see below) to contribute to the documentation among herders of traditional knowledge about snow leopards.

The Land of the Snow Leopard Network – Reaching for the Stars

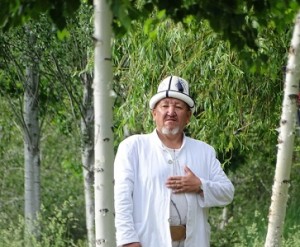

In our Network are keepers of the ancient wisdom, including Kyrgyz Elder and Sacred Site Guardian Zhaparkul Raimbekov, Buryat Buddhist leader Norbu Lama, Mongolian Shaman E. Buyanbadrakh, Altaian Shaman and Guardian of Sacred Irbis Tuu (Snow Leopard Mountain) Slava Cheltuev. For convenience, we refer to them as Indigenous Cultural Practitioners (ICPs). They communicate with the spirits, (or creator, or ancestors, or guardians—all these terms have been used in translations of our discussions). Buyanbadrakh, for example, received his Shamanic skills from seven of his ancestors. From these entities, the ICPs receive invisible information, visionary dreams, or support and guidance to help an individual or community.

You could say, then, that our Network is reaching for the stars, bringing together these ICPs, along with other wisdom-keepers: lifelong herders who know the ancient practices for reading and living in their environment; Indigenous educators, historians, and traditional hunters striving to maintain or revive their cultures; a handful of boots-on-the-ground natural scientists; and two progressive grant foundations—all in an effort centered on protecting snow leopards.

Our goals are the revitalization of cultures in our program area, and the integration of Indigenous Knowledge into mainstream planning for snow leopard conservation.

Our Workshop Venue – Talas, Kyrgyzstan

Daniar and Gulmara operate the Bai Bol Ethno Complex, our home for the weeklong workshop, just outside the Talas town center. This couple, like some 70% of Kyrgyz people, are Muslim, and as it was the beginning of Ramadan, they were fasting from sunup to sundown. Ours was the first international workshop they had hosted, and they worked hard to make sure everything was satisfactory.

Daniar and Gulmara operate the Bai Bol Ethno Complex, our home for the weeklong workshop, just outside the Talas town center. This couple, like some 70% of Kyrgyz people, are Muslim, and as it was the beginning of Ramadan, they were fasting from sunup to sundown. Ours was the first international workshop they had hosted, and they worked hard to make sure everything was satisfactory.

Daniar plants peonies in honor of his mother; they are her favorite flower. As the week progressed and we got to know each other, I realized that they are particularly knowledgeable about the history of the Talas region; they keep a small museum, and they were very interested in our Network and its goals. When I went to pay the bill, it reflected a substantial discount, which they wanted to give in celebration of the holy month.

LOSL Network App

For the past two years the LOSL Network has been developing a custom App for use by remote communities in monitoring wildlife and collecting data in a way that supports the needs of local communities as well as the goals of the Global Snow Leopard & Ecosystem Protection Plan (GSLEP). Read more about the GSLEP here.

Last year’s testing of the App revealed the need for changes that would make it easier to use. We also needed to discuss data security and other practical issues in maintaining the network and ensuring its sustainability.

The Collaborative Snow Leopard Conservation Program

LOSL is one of seven projects/partners working under a three-year grant with the working title of “Collaborative Snow Leopard Conservation Program.” Coming up with a name for the collaborative was another of our tasks. Once the other partners add their suggestions, a vote will determine the winner. The name will also identify a website being developed to disseminate information and educate the public about our collaborative work.

A report on the LOSL workshop will be forthcoming, for those who love details! For me, one of the main take-aways from our discussions was the commonalities across our Network, and how the stories, legends, and traditions that will make up the LOSL “cultural database” can be used in several powerful ways, including the forthcoming website, to have a real impact on snow leopard conservation.

A Visit to Sacred Sites

When 30 people put their heads together in these deep discussions, it’s essential to take breaks, to get out in nature and remember why we are so determined to create these pathways for Western and Indigenous science to unite around the Snow Leopard.

Zhaparkul, who lives in Talas, was our guide on these outings. He is a guardian of the nearby sacred sites, and is deeply involved in their preservation and in educating people about them.

Zhaparkul, who lives in Talas, was our guide on these outings. He is a guardian of the nearby sacred sites, and is deeply involved in their preservation and in educating people about them.

Besides our visit to the Manas Historical Park, Zhaparkul took us to a sacred spring spring site—actually a series of springs—named after Manas’s wife Kanykei, and her daughter-in-law Ai’chürök. Zhaparkul explained that the waters of the first spring can protect us from the Evil Eye, and that he would do a special blessing for each of us. The blessing is most effective if the subject doesn’t see the water coming, if they are startled.

Besides our visit to the Manas Historical Park, Zhaparkul took us to a sacred spring spring site—actually a series of springs—named after Manas’s wife Kanykei, and her daughter-in-law Ai’chürök. Zhaparkul explained that the waters of the first spring can protect us from the Evil Eye, and that he would do a special blessing for each of us. The blessing is most effective if the subject doesn’t see the water coming, if they are startled.

Needless to say, there was a lot of laughter during these blessings! It was a warm day, and it was so pleasant sitting on the grass, none of us wanted to leave.

Our next outing was a visit to the Sacred Site of Arashan, which lies at the entrance to Besh Tash National Park. The springs here have also been known since ancient times. Arashan means Sacred Mineral Water. In the Buryat language, Arashan means Sacred Spring, and in Tajik, it means Sun Ray. Interestingly, if I understood correctly, the founding ancestor of the spring disappeared, in a ray of sunshine, after living many centuries.

We were greeted by a couple who came to be caretakers of Arashan after visiting the springs as pilgrims, and seeing that the place was being trashed by visitors, they saw the need for protection. They have several businesses and some land. Profits from those are invested in Arashan. There’s no fee, but they accept donations, which cover 15-20% of their costs. They hear from the spirits of the spring what they need to do whether it’s to move stones to a particular place or what to plant or other questions about the gardens; they consult the spirits.

People come to the springs from all over the world, as a last resort, but the healing is effective. They explained that these springs are different from other sacred sites; people get a vision from the spirits. Artists and scientists get inspiration.

I got a sense of what they meant when we visited the first spring and following Zhaparkul’s prayer a feeling of calm washed over me. The trip had been marked by difficulties over money; failed wire and Western Union transfers, ATM and credit cards that didn’t work in Bishkek, the bank’s rejection of any US bill that had a wrinkle or ink stain. Since I was responsible for all payments, it had been extremely stressful. But suddenly I knew it would all work out okay.

At the Spring of Love and Tenderness, Zhaparkul explained that he wanted to give Rodney and me a special blessing in honor of our many years of working with indigenous communities to save snow leopards. That experience in a beautiful shady forest with the clear pool of the spring and Zhaparkul’s powerful voice in counterpoint to the rippling of the nearby stream is one I will never forget.

At the Spring of Love and Tenderness, Zhaparkul explained that he wanted to give Rodney and me a special blessing in honor of our many years of working with indigenous communities to save snow leopards. That experience in a beautiful shady forest with the clear pool of the spring and Zhaparkul’s powerful voice in counterpoint to the rippling of the nearby stream is one I will never forget.

The keepers of the site had invited some local volunteers to meet us, including a park ranger who had come to Arashan for a teacher training workshop and became involved in the volunteer movement to protect the springs. He thinks the movement is gaining momentum. Our visit provides a platform for cooperation, not only to save snow leopard but also other wildlife.

Rodney asked about snow leopards and was told that a herder had seen one way up the canyon, behind the third bridge. Later, Rodney and Norbu hiked up the canyon from the springs and came upon a large boulder where a snow leopard had made a scrape to mark its presence. We thought that was an excellent sign or blessing of our work.

From Arashan, we drove deeper into the park. Akylbek wanted to show us the place where he set his camera traps. Unfortunately, the bridge there had been washed away, and we couldn’t cross the river to get to the cameras.

Eagle Hunters & Dog Racing

We were late getting back to the Bai Bol where we ate a quick dinner and headed back out for a presentation by Salburun, the local Eagle Hunters’ Association.

What fun that was as everyone took turns holding such a magnificent creature—even though it was the birds’ time of molting and the hunters wouldn’t be able to demonstrate how they work with the horsemen and Taigans (traditional hunting dogs).

We also each got a turn at trying to hit the target with the traditional bow. The women ruled! We did note that the bows were made much thinner than the ancient ones we had seen in the Manas Museum.

The hunters wanted to demonstrate the Taigan’s abilities, so they dragged a hide bundle behind a very fast horse and turned the half-dozen dogs loose to give chase. By the time the horse reached the end of the field, the grey Taigan had overtaken the horse.

In fact, our hosts were the Taigan jarysh (dog racing) champions of the recent Second World Nomad Games (worldnomadgames.com/en/).

In that official race, the course was 350 meters; 19 athletes competed, from Georgia, Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. While the horse gets up to a speed of 60-65 km/hr., the fastest dog is the winner. In 2016, Kyrgyzstan won all the medals: gold, silver, and bronze.

Traditional Cultures, the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Program, & the Support of the President of Kyrgyzstan

The President of Kyrgyzstan, Almazbek Atambayev, had opened the games with the comments, “In the modern world, people are forgetting their history, and there is a threat of extinction for traditional cultures. Nomadic civilization is an example of sustainable development, which is what all of humanity is looking for today.”

This is the same President who has led the GSLEP effort; he understands the work of our LOSL Network, especially in the context of the GLSEP mandate to “Enhance the role of local communities in snow leopard conservation efforts by adopting and implementing policies and laws that favor the involvement of such communities as stewards of biodiversity and champions of conservation.” (globalsnowleopard.org). His support has been invaluable.

Many thanks to Lyubov Ivaskina and Nicolas Villaume for sharing their great photos!