Photo: Jak Wonderly

Snow leopards have had a number of names since they first came to the attention of Europeans. The word, “leopard” comes to us from two Greek words that mean leon pard or lion cat. Words change over time, and so the “n” slipped away and the two words slammed together. In a similar way, snow leopards were once known as ounce. The name might come from Latin: luncea which means lynx. In French the word became lonce which was altered over time to l’once because French speakers thought the “L” meant “the.” Eventually, the “L” fell off and the name became, simply, once and that became, in English, ounce. These days, among English speaking people, snow leopards are most commonly known as… snow leopards, but they have many other names – among them are léopard des neiges (French), Schneeleopard (German); and leopardo de las nieves (Spanish). And in the languages of the countries where the snow leopard lives, they are known as xuě bào (Chinese), Barfani chita (Hindi, Urdu – Pakistan), shan (Ladakhi – India), heung chituwa (Nepali), ilbirs (Kyrgyz), irbis (Kazakh, Russian, Mongolian), sah, shen (Tibetan); chen (Bhutanese), and palang-i-berf (Dari – Afghanistan).

The scientists who think about what to call all living things have, themselves, been given a name. They are called taxonomists. Taxonomy is the orderly classification of plants and animals according to their presumed natural relationships. In other words, taxonomists try to group living things with other, similar, living things. It’s a way of knowing who is related to whom. Sometimes, as we will see, it isn’t easy.

Taxonomists place the snow leopard in the Kingdom Animalia because they are animals, not plants or bacteria. They are placed in the Phylum Chordata because they have spinal cords unlike crabs or jellyfish, for instance. They are further placed in the Class Mammalia because they have fur as all mammals have either hair or fur, and they nurse their young. They are then placed in the Order Carnivora because they only eat meat. And snow leopards are placed in the Family Felidae who we commonly call cats.

At this point, classifying the snow leopard becomes more difficult. They weren’t originally placed in the genus Panthera that’s made up of the tiger, lion, jaguar, and leopard because of their inability to roar due to differences in their anatomical structure. However, recent phylogenetic or evolutionary analyses that are based on similarities and differences in physical or genetic characteristics do place the snow leopard within the genus Panthera, being most closely related to the tiger Panthera tigris. The two species split apart about 2 million years ago. So, now, the snow leopard is known as Panthera uncia.

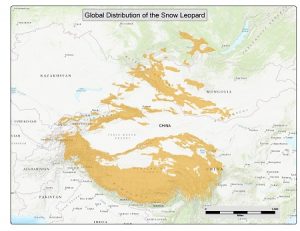

Snow leopards are found in the mountains of Central Asia. Their range includes the Himalayan mountains of Nepal, India, and Bhutan; Pakistan’s Karakorum and Hindu Kush; the high mountain ranges of Afghanistan, Mongolia, the People’s Republic of China, Russia and the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Snow leopard habitat is rugged and remote. These endangered big cats can even be found at the base of earth’s highest mountain, Mt. Everest, called Chomolungma by the people who live around it.

Snow leopards are found in the mountains of Central Asia. Their range includes the Himalayan mountains of Nepal, India, and Bhutan; Pakistan’s Karakorum and Hindu Kush; the high mountain ranges of Afghanistan, Mongolia, the People’s Republic of China, Russia and the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Snow leopard habitat is rugged and remote. These endangered big cats can even be found at the base of earth’s highest mountain, Mt. Everest, called Chomolungma by the people who live around it.

Photo: Tashi R. Ghale

Within their mountain habitat, snow leopards like high, steep and rocky places where there are few plants, places that scientists call the alpine and sub-alpine zones. Snow leopards live in the alpine zone in the warmer, summer months of the year. They come down into the sub-alpine zone in the colder, winter months following the animals that they hunt for food – the bharal or the ibex, that come down to lower elevations in search of winter grazing.

Photo: Tashi R. Ghale

The answer to this question is closely linked with the answer to the question, “Where do snow leopards live?” Snow leopards look the way they do as a result of adaptations to their environment. To put it another way: snow leopards look the way they do because of where, and how, they live.

Photo: Tashi R. Ghale

Snow leopards are well adapted to their high altitude homes where they may encounter deep snow and rocky terrain with little vegetation. Snow leopards have a well-developed chest that helps them draw oxygen from the thin air of the high mountains. Snow leopards also have short forelimbs with snowshoe-like paws, long hind limbs, and a tail nearly a meter long. These adaptations help them balance on rocky precipices and navigate deep snow.

Adaptations for cold include an enlarged nasal cavity that allows them to warm the cold air they are about to take into their lungs. Other adaptations for cold include long body hair with a dense, woolly underfur and a thick tail that can be wrapped around the body.

The snow leopards beautiful pelage enables them to blend into their surroundings.

Photo: Steve Tracy

Snow leopards are the smallest of the big cats. From their nose to the base of their tail, they measure about 39-51 inches (100-130 cm). Their tail, which is the longest of any felid when compared to their body size, measures 32-40 inches (80-100 cm). It acts as a rudder as they run up and down steep rocky slopes and leap from rock to rock. Snow leopards weigh between 55 and 115 pounds (25-52 kg). As far as their proportions, they resemble a cheetah in that they have long hind limbs, which gives them a longer stride and faster running speeds. The snow leopard’s large paws, which act like snow shoes, measure about 4 inches long by 3 inches wide (10 x 8 cm). Snow leopards have the longest and thickest fur of any of the big cats which helps to keep them warm during the brutally cold winters, and they use their long tails to wrap around themselves like a muffler. Their fur color varies from white to cream to pale yellow or gray, sprinkled with rosettes (spots) of charcoal-grey to black. Each snow leopard has its own distinctive marking pattern. The snow leopard’s beautiful coat gives it the advantage of camouflage while hunting by being able to easily blend in with the rocks and snow.

Photo: Steve Tracy

How do the biologists tell the difference between these two cats? Well, the answer is in their pelage, or the complex variability in their markings similar to our fingerprints. They use unique spot patterns in the snow leopard’s pelage to identify them. In documenting the pelage of a snow leopard, both main features and secondary features of the pelage may be noted. But a snow leopard’s fur patterns may change a bit as they mature.

Unlike the other big cats, the snow leopard is unable to roar. It’s larynx differs anatomically in that it does not have the fibroelastic ligament that is necessary for roaring. The snow leopard isn’t silent though. In fact, it is capable of making a variety of other vocalizations, including puffing, hissing, growling, screaming, yowling, moaning, and even purring. It’s distinctive main call made during the breeding season is easily heard as it reverberates off the cliffs and across the valleys.

Snow leopards are one of the top predators in the high mountain food web of Central Asia. The snow leopard is an opportunistic predator capable of killing prey three times its weight.

Blue Sheep – Bharal

Snow leopards in the Himalaya and Tibet eat blue sheep (bharal) Pseudois nayaur.

Siberian Ibex

Snow leopards that live in the Karakorum, Tien Shan, Mongolian and Russian mountain ranges eat Siberian ibex Capra sibirica.

Woolly Hare

Blue sheep and ibex are the snow leopards favorite meal, but they also eat small prey such as woolly hares, pika, marmots, and birds.

Marmots

Snow leopards help to keep the ecosystem in balance by preying on Himalayan marmot populations. Marmots are important to the alpine pastureland because their burrowing, much like plowing, aerates the soil and helps the grasses grow. The grasses are important to the wild sheep and goats which are also snow leopard prey and also to the livestock that mountain people depend upon for their existence. However, marmots also eat vegetation, and they have periodic population explosions. Too many marmots, eating too many grasses and shrubs, will degrade the alpine meadows.

By preying on the wild sheep and goats, snow leopards also help to keep the meadows healthy. Overgrazing by too many marmots, like overgrazing by too many ungulates, kills the grass and shrubs. If predators are removed the grassland could disappear causing the wild ungulates (ungulates are hoofed animals) and marmots to disappear. Then the butterflies and other insects that pollinate the meadows and the barley and potatoes that people eat would also disappear. This is an example of the domino effect in nature.

All these factors tell us that snow leopards are not only a beautiful symbol of the high mountains of Central Asia, they are an indicator species. Where they are healthy we can expect to find a healthy ecosystem. Where they are struggling we can expect to find the whole web of life on shaky ground.

Snow leopards are capable of running very fast for short distances. However, the ability to run fast is not a particular adaptation of this big cat. The fastest cat, the cheetah, lives in open habitat where it is difficult to sneak up on prey. The cheetah instead uses speed to catch its dinner. Snow leopards live in craggy, mountainous areas, and they usually have to rush their prey at short distances. The ability to leap, bound and pounce have become this cat’s adaptations. Snow leopards have been known to leap as much as 30 feet.

Photo: Peter Bolliger

In both running and leaping, the snow leopard is highly dependent on its tail for balance, and it is a tail unmatched by any other cat. It is covered with amazingly long, dense fur which makes it appear very thick.

Female snow leopards usually give birth to 2 or 3 cubs with a rare occurrence of 4 or 5 in a litter. The mating season is January through March, with births occurring from April to June, following a 90 to 105-day gestation period. The cubs will generally stay with their mother for 18 months up to 2 years.

Mother snow leopard and her two cubs, Nepal. Photo: Tashi R. Ghale

Photo of a mature Shynghyz: Steve Tracy

In captivity, snow leopards have been known to live to 21 years. Their lives in the wild are much harder and are consequently much shorter. The oldest adult in the wild was recorded to have lived 11 years. But there is a lack of scientific data to know for sure what is the average lifespan of a wild snow leopard.

The snow leopard faces a wide spectrum of threats. One of these is lack of awareness of its value to the environment and to the local communities as a cultural and spiritual icon.

Another threat is loss of and disruption of its habitat. Due to an ever-encroaching human population, the snow leopard must deal with a shrinking habitat. The snow leopard’s range countries are experiencing rapid economic growth and with that comes development in infrastructure such as the building of roads and rail lines, dams for harnessing hydroelectric power, and mining not only for gold, semi-precious stones, and minerals but also for natural resources like oil and natural gas. In addition, fences and barriers are being built along international borders. These are a challenge to a species that doesn’t recognize boundaries and borderlines.

Reduction in wild prey is another challenge the snow leopard faces. This is due in part to illegal or poorly managed trophy-hunting programs. But it is also due to wild sheep and goats having to compete for grazing land with domestic animals.

Snow leopard pelt.

A serious threat to the snow leopard is illegal poaching. The bones, skin, and organs of large cats are valuable in traditional Asian medicine. Tigers are the preferred species for this purpose, but they are now so rare that it is almost impossible to find one in the wild so snow leopards are substituted for tigers. When you consider that the people who live near snow leopards often earn less than 300 dollars per year and that a poacher can get perhaps $200 for a dead snow leopard (though a middleman can resell it for up to $10,000), it isn’t hard to understand why snow leopards are at risk.

Poacher’s snare. Photo: S. Spitsyn

In addition, snow leopards are at risk due to secondary or “by-catch” snaring and poisoning that is meant for other species. And a recently recognized yet increasing cause of deaths is the result of attacks by feral dogs with whom snow leopards also compete for prey.

Snow leopards and their prey as inhabitants of cold, dry environments may be particularly susceptible to disease carried by domestic and other wild animals, transmitted either through direct contact or parasitic infestations. Though there is little recorded information, there have been reports of diseases in wild snow leopards such as canine distemper, feline leukemia, tuberculosis, and anthrax, among others, including one lone report of rabies in the 1940s.

Of an indirect nature, human military conflicts within the snow leopard’s range can have an effect on population numbers. However, the ever-increasing worry of the effects of the changing climate on the mountain ecosystem are of more concern.

Climate change will have extreme effect on the biodiversity of our planet because of changes in habitat. This has already been noted in mountainous regions. For example, with climatic warming, the permafrost layer that lies beneath most of the snow leopard’s range will warm. This will result in a lowering of the water table, which will transform lush meadows into less-productive grasslands. Springs, streams, and ponds will begin to disappear. And the tree line is expected to advance to higher elevations. All these habitat changes will result in smaller populations of the wild prey species the snow leopard depends on for food and of equal concern, will lead to fragmentation of the entire habitat. This would have a deleterious effect on the species as a whole by isolating individual snow leopards from one another, reducing the genetic diversity that maintains the health of the species.

In addtion to disruption of the habitat, weather extremes are also expected with the changing climate, including droughts, extremely heavy, late, or early snowfalls, and partial melting and freezing of snow; all of which could result in high mortality of prey species and act as serious deterrents to successful mating and cub rearing.

The most prevalent threat to the snow leopard is conflict with people. This conflict arises because of depredation by snow leopards on livestock and sometimes results in retaliatory killing. But why do snow leopards prey on domestic animals?

The local agropastoral human communities are dependent on their flocks of sheep and goats for their livelihood. However, as those communities grow and expand, so do their flocks. The resultant overgrazing by large domestic flocks damages the fragile mountain grasslands, leaving less food for the wild sheep and goats that are the snow leopard’s main prey. With less food for the wild sheep and goats, there will be fewer of these animals for the snow leopard. This leaves the snow leopard with little choice but to prey on the domestic livestock for their own survival. An unhappy herdsman, arriving at his goat pen one morning to find that all of his goats have been killed, might retaliate by killing the snow leopard if he can find it.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is a world-wide membership union made up 0f 1300 governmental and non-governmental organizations and more than 14,000 experts. It was created in 1948 and has become the largest repository of environmental knowledge regarding the status of our natural world and what is being done to protect it. The IUCN provides information about range, population size, habitat and ecology, use and/or trade, threats, and conservation actions that will help inform necessary conservation decisions.

The IUCN has defined the criteria that identifies species that are at risk of extinction. The snow leopard is listed as Vulnerable with a population that is decreasing on the IUCN’s “Red List of Threatened Species.”

CITES is a second organization that attempts to identify animal species that are at risk. CITES is the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. CITES bans or strictly limits trade of animals or their body parts. Since 1975, the snow leopard has been listed by CITES in Appendix I, which includes species that are threatened with extinction. This means it is illegal to internationally trade in snow leopards or their body parts.

All of the 12 snow leopard range countries participate in the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP) that brings together both governmental and nongovernmental organizations with representatives from the local communities, including spiritual leaders, in an effort to conserve snow leopards and their valuable high-mountain ecosystems.

Despite the efforts of TRAFFIC, snow leopard skins can still be found for sale in some of the snow leopard countries. Also, the bones, skin and other organs of snow leopards are substituted for tiger parts in Asian traditional medicine. The cats are protected by law in nearly all twelve range countries, but it is almost impossible to enforce the laws in the snow leopard’s remote mountain habitat. They are listed in Appendix I (most endangered) of the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which bans or strictly limits trade of animals or their body parts.

As of November 2016, the IUCN estimates there are between 2710 and 3386 snow leopards living in the mountains of central Asia. The Snow Leopard Conservancy’s 2010 estimate is a bit larger, being between 4500 and 7500 individuals. And yet another estimate by McCarthy & Chapron from 2003 is between 4,080 and 6,500. And it is believed that 60% of the entire population of snow leopards live in China. The rough estimates shown here have been based on limited surveys. Because snow leopards move across boundaries, they may have been counted twice. Reports of sightings or the sign they leave in the environment can be misleading. In some areas, for instance where wars have been fought, there may be fewer cats than in past decades. In other areas where snow leopards are being protected, their numbers may have grown. Because of the difficulty of studying snow leopards we do not know what their historical population might have been. New technologies such as DNA analysis and camera traps will allow researchers to make better estimates. In time we will have the data that will tell us whether the snow leopard’s numbers are growing or declining. For now, we can only guess.

Estimated snow leopard populations: |

|||

Afghanistan |

100 – 200 |

||

Bhutan |

100 – 200 |

||

Burma/Myanmar |

No Studies |

||

China |

2,000 – 2,500 |

||

India |

200 – 600 |

||

Kazakhstan |

180 – 200 |

||

Kyrgyzstan |

800 – 1400 |

||

Mongolia |

500 – 1,000 |

||

Nepal |

350 – 500 |

||

Pakistan |

250 – 420 |

||

Russia |

50 – 150 |

||

Tajikistan |

120 – 300 |

||

Uzbekistan |

10 – 50 |

||

Total |

5,060 – 7,220 |

||

Tama Zoological Park – Tokyo. Photo: Steve Tracy.

There are approximately 600 snow leopards living in 160 accredited zoos worldwide including approximately 118 in 53 accredited American zoos. Suitable mates are selected under the guidance of the Species Survival Plan for snow leopards.

The American Zoo and Aquarium Association’s Species Survival Plan program was initiated in 1981, and includes a plan for snow leopards. Under this program, zoos cooperate to manage individual animals as a single population. While this program will ensure that snow leopards do not become extinct, reintroducing snow leopards into their natural habitat is not a viable option at this time. We need more information about their status in the wild. Their habitat must be preserved. We must work on the problems of conflicts between people and wildlife.

The Snow Leopard Conservancy is working to make it possible for snow leopards to continue to live in the mountains of central Asia, their home. We try to achieve this goal in as many ways as we can imagine. Here are three of those ways:

-

Dr. Rodney Jackson speaks with a participant at the WCN Spring Expo at Brookfield Zoo. Photo: SLC

We study snow leopards in the field to learn everything we can about them. At the same time, we train local wildlife biologists and conservationists so that in future they can do this work themselves. We pass what we’ve learned on to anyone who is interested, especially other scientists and students. We do this by publishing scientific papers, by participating in conferences, and through speaking engagements. This website is another way we pass along what we’ve learned.

Predator-proofed corral. Photo: SLC-IT

-

We go to the people who live near snow leopards and learn what they need to reduce conflicts between people and cats. Then we work with them on solutions such as building and maintaining predator proof corrals to keep their animals safe from snow leopards.

-

Himalayan Homestay site. Photo: B. Sharaf

The high mountain home of snow leopards is one of the most beautiful places on earth. Because of its beauty, and because snow leopards live there, it is a place that adventurous tourists want to visit. The Snow Leopard Conservancy helps local people develop lodging for people who are traveling through snow leopard lands. Called home stays, these lodgings are rustic “bed and breakfast” accommodations where travelers can meet local people, learn about local customs, enjoy local foods, and hike with expert local guides who show them around the nearby countryside. There is always a chance the traveler will get to see a snow leopard! The money local people receive for these services helps offset snow leopard depredation and makes the snow leopards an asset rather than a liability.

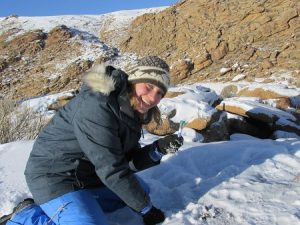

Snow Leopard Reseacher, Katey Duffey, studying snow leopards in Mongolia.

Most entry-level zoo keeper positions now require a four-year college degree. Training in animal science, zoology, marine biology, conservation biology, wildlife management, and animal behavior is preferred. Curatorial, research, and conservation positions typically require advanced academic degrees. However, advanced academic training by itself is insufficient, and it may take years of “on-the-job training” for someone to learn the practical aspects of exotic animal care. A few institutions offer curatorial internships which are designed to provide practical experience. For working in the wild, a Master of Science degree in zoology, animal behavior or wildlife management would be required.

Sources:

- Snow Leopards. Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes.

- Section 1. Defining the Snow Leopard. Compiled and edited by P.J. Nyhus, T. McCarthy, and D. Mallon.

- Chapter 1. “What is a Snow Leopard? Taxonomy, Morphology, and Phylogeny.” Written by Andrew C. Kitcherner, Carlos A. Driscoll, and Nobuyuki Yamaguchi.

- Chapter 2. “What is a Snow Leopard? Behavior and Ecology.” Written by Joseph L. Fox, and Raghunandan S. Chundawat.

- Section 1. Defining the Snow Leopard. Compiled and edited by P.J. Nyhus, T. McCarthy, and D. Mallon.

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- CITES.

- Global Snow Leopard & Ecosystem Program.

- Snow Leopard Conservancy.

- Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, Wild Cats, compiled and edited by Kristin Nowell and Peter Jackson, IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, 1996.