In remote Annapurna (Nepal) in the Spring of 2011 — one of the remote cameras captured an adult snow leopard named Mukti, literally meaning “liberty”, along the slopes of Muktinath (holy pilgrimage site) situated at the elevation of 4,000 meters. [Muktinath is considered a salvation valley for Hindu people and also a religious site for Buddhists]. Ghirmi Gurung, the village chief of Lubra, who was installing remote cameras and monitoring snow leopards, had no clue that the elusive cat was female until it was captured later in yet another camera. This time, Mukti was with a newborn!

Ghirmi, in his lifetime, has encountered snow leopard three times. An incident, which he cannot forget, still lingers in his mind.

“Four years ago,” he reminisces, “it was there munching in a place called ‘Jara in Yapo.’ Ghirmi had gone to gather the yaks in the high pastureland. “It was my uncle’s horse,” he recalls, “Forty meters away, an adult snow leopard was eating up the black horse worth ninety thousand Rupees ($1,000)!” On returning to the village, he shared what he witnessed, with his uncle. Ghirmi knew the old man’s temper, and was worried that he would do something adverse in anger. Consoling someone was not a custom then, however, he was able to calm the old herder down.

Ghirmi says that many livestock have become the victim of predators, more so for the last few years. The chief of Lubra village, Ghirmi, in his early thirties, reveals that 30-35 horses have been killed this year alone.

“Yak calves are the target,” Ghirmi says, “sometimes it is the snow leopard that kills the animals while other times it may be the common leopard.”

Common leopard captured on remote trail camera (SLC/NTNC)

Common leopard captured on remote trail camera (SLC/NTNC)

But villagers, he says, blame the snow leopard for all the killings, largely because they do not believe common leopards ascend up to the height of 3,000 meter and above. This long-held belief disappeared from the villagers when a remote camera revealed several well framed-images of a common leopard.

“Thanks to Snow Leopard Conservancy we now know that common leopards also visit our mountains!” Ghirmi says. “I showed villagers the leopard photos,” he explains. “It caught skeptics by surprise!” he amuses.

“It’s challenging to console poor herders when they lose a baby yak or a horse to snow leopard,” Ghirmi says, “Horses are pretty expensive. There is now support coming from ACAP (Annapurna Conservation Area Project),” he states, “Under which, if a predator kills and leaves behind the carcass, we receive a compensation of 10-15% of what the animal was worth when alive. But Ghirmi thinks many people are still not aware of this provision.

Ghirmi Gurung (nearest camera) with Snow Leopard Scouts (SLC/NTNC)

Ghirmi Gurung (nearest camera) with Snow Leopard Scouts (SLC/NTNC)

Ghirmi’s journey to the path of snow leopard conservation started with Snow Leopard Scouts Environmental Camp when he, among others, learned to characterize snow leopard signs such as scrapes. He assisted in snow leopard research undertaken by Snow Leopard Conservancy in his village in 2010. He helped in delineating seasonal grazing pastures and counted blue sheep, along the slopes of Muktinath valley. Upon seeing his excellent performance, he was invited to participate in the environmental exposure camp and snow leopard monitoring venture in 2011. Ghirmi has been one of the active performers in snow leopard street-drama. He excellently played a role of a village leader known as Mukhiya. His performance as Mukhiya was highly applauded. Ghirmi is indeed Mukhiya, in his real life! Ghirmi has been conveying the message that snow leopard must not be prosecuted merely because at times it raids the livestock. “It has its own right to live like any of us humans,” he has declared in many social gatherings.

Today, as the conservation committee chairperson for Muktinath, Ghirmi has been active in helping villagers build predator-proof corrals, guide herders’ meetings, and monitor region’s wildlife and other natural resources. [Fifty-six village level conservation area management committees, CAMC, regulate Annapurna Conservation Area’s wildlife and other natural resources at the local level.] Ghirmi explains to his fellowmen in the village in meetings and gatherings about the important role of snow leopards in maintaining biodiversity and why herders should guard their livestock in open pastures. “CAMC has prohibited cows and goats of the village into the open forests to avoid attack from predators,” he shares.

An owner of 110 goats, 2 yaks and 5 cows, Ghirmi himself shepherded his herd of sheep and goats continuously for a year. “These days,” he explains “the young generation does not want to be herders.” Therefore, there is an acute lack of herders in the village. “The practice of livestock herding is slowly dying,” he worries.

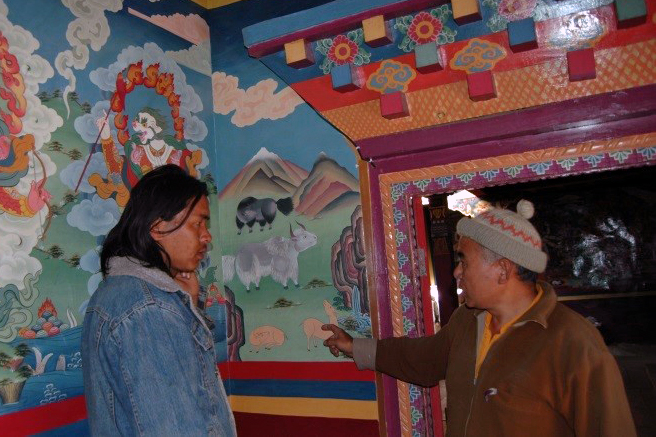

Ghirimi Gurung and village head lama (SLC/NTNC)

Ghirimi Gurung and village head lama (SLC/NTNC)

Ghirmi has special affinity toward the snow leopard – perhaps because he belongs to the tribe that has long a long held tradition to appease the snow leopard as ancestral spirits. His village Lubra, home to the only Bon School and monasteries in Nepal, was founded in the 12th century by Trashi Gyaltsen, the son of a Bon-Po lama from Tibet, who had outstanding debating abilities outwitting the Buddhist monks. The legends has it that both Bon-Po and Buddhist deities, disguised as snow leopard, are believed to travel from one place to another guarding the village territories from demons and natural calamities. So killing a snow leopard may mean harming your own ancestral spirits! Ghirmi, an avid Bon-Po follower, believes that this is one important reason why we should protect snow leopards. Just four years ago, a snow leopard entered into his village. “That was dramatic,” he begins sharing his experience. “Perhaps the cat was hungry, it climbed straight up our only communal livestock shed in broad day light,” he vividly tells what happened that day. “It created chaos, people hooting, hollering at the top of their voice, finally chased the beast away from the corral,” he adds. Out of confusion, to everybody’s amazement, the leopard, instead of running toward the cliff, hurriedly climbed up the nearby roof, and jumped from one roof to another, and finally fled towards the cliff. “That was quite a scene,” he chuckles.

Working on snow leopards for the last four years, Ghirmi’s experience allows him to roughly estimate where snow leopard resides. “During the cold, it comes down as low as 3,000 meters in search of its prey. This can be guessed by it pugmarks and scats they leave behind,” he reveals.

Ghirmi opines that it is important to mobilize local youths in monitoring of snow leopards, “because in another 20-30 years, it is the youth who will run the show,” he says.

“Being an important local person with such an avid interests in snow leopard, an individual like Ghirmi can be a resource person for snow leopard conservation for a long time to come”, says Suresh Thapa, a Senior Ranger at ACAP Jomsom Station.

-Anil Adhikari and Bikram Shrestha, SLC-Nepal Program