By Ashleigh Lutz-Nelson, Executive Director

One step at a time. That is what I keep telling myself as I climb one step closer to the summit of Kang La Pass at 17,454 ft. If anyone would have told me growing up at sea-level in Florida that I would climb nearly the height of Everest Base Camp, I’m not sure I would have believed them. Reflecting on the irony and pure magic of the situation at hand, I smile, looking out at glacier level over the spectacular roof of the world. The air is so thin here that I must stop every 50 meters or so to reoxygenate my muscles to keep going. Almost there. One foot in front of the other.

Photo – Suzi Eszterhas

Everywhere I look across the remote terrain, a perfectly camouflaged crouching snow leopard could be concealed, looking back at me. I can feel its presence. I can see it in the pugmarks, scat, and scrape signs as I walk the same path it has walked before me. I imagine how much easier it would be if I was a majestic snow leopard walking effortlessly along these steep precarious trails. I imagine each of the faces of the beloved snow leopards in my care at the zoo watching me curiously and patiently as if thinking – What will she do next?

A few days prior, Snow Leopard Conservancy (SLC) and International Veterinary Outreach (IVO) finished hosting animal health and conservation workshops with Nepali partner organization Mountain Spirit (MS) in the Nar Phu Valley in Annapurna Conservation Area. It was my first time traveling to this unique cultural and biodiverse landscape, home to traditional Tibetan Buddhist agro-pastoralist communities, their domestic herds, snow leopards, Himalayan wolves, blue sheep, Himalayan vultures, lammergeiers, and many other species in this wondrous high mountain ecosystem.

The Conservancy has been working in Nepal’s Nar and Phu Valleys (and Sagarmatha National Park, Mt. Everest) under the Darwin Initiative the past four years. Despite significant challenges with the pandemic and associated national lockdowns, natural disasters affecting road access, and human-predator conflict, these communities have made significant progress toward coexistence with snow leopards.

For example, in spring of 2021, there was a mass depredation incident when, over the course of one evening, a snow leopard killed over 50 goats and sheep within a traditional corral. One of SLC affiliates, Kamal Thapa, was working in the Phu village at the time. With support from Annapurna Conservation Area Project wildlife officials, he was able to facilitate the release of the snow leopard stuck in the corral within 24 hours. Luckily, the cat’s life was spared, but the herders were left with severe economic and emotional hardship. The next evening, the snow leopard returned and killed 12 more livestock in another nearby traditional corral, as it was still hungry from not eating after the hunt the evening before.

Fortunately, the Narpa Bhumi Rural Municipality helped facilitate prompt compensation for the significant losses, providing economic relief from the disaster, which was compounded due to the multiple existing hardships of the pandemic, loss of incomes from lack of ecotourism, and natural disasters that occurred the same year. The forgiveness shown to the snow leopard by the community members is a significant shift toward coexistence with the big cat.

In 2020, our veterinary team had planned to host livestock health and husbandry workshops in these communities to help reduce depredation losses and potential retributive killings of snow leopards. Due to the pandemic safety restriction delays, we were not able to do so until now. Over the last two pandemic years, SLC and MS adapted conservation activities under the Darwin Initiative project to include emergency relief for the communities, such as addressing food and medicine scarcity, providing Foxlight predator-deterrents and facilitation of alternative income activities (such as Jimbu, Himalayan chives) to offset ecotourism decline and snow leopard attacks on domesticated livestock.

During the three days trek to the Phu village, located near the Tibetan border, we saw nine herds of blue sheep and Himalayan vultures and lammergeiers flying high above the ridgelines. As we trekked up to the village gate, a herd of hard-working mules carrying supplies from a three days’ journey from the road in Chame hurried past us toward the village of flat roofed, stone-walled stacked dwellings.

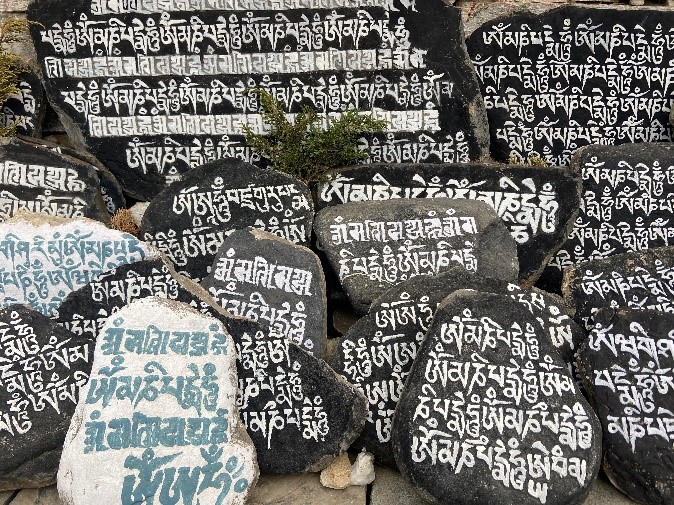

Entering through the ancient gate high in the sky to Phu Village (14,000 ft elevation) felt like stepping back into a time centuries ago looking over a fortress etched into the mountains. Inscribed over the gompa (a Tibetan monastery or temple) were the words, repeatedly: Om Mani Padme Hum, a Sanskrit mantra that literally translates to ‘praise the jewel in the lotus.’ It is recognized as an expression of love and compassion of all the Buddhas. One of our team members saw snow leopard pugmarks in the snow not far from the gate and we knew we were entering into prime snow leopard habitat!

The workshops took place in the Nar and Phu communities, led by our team, which included IVO’s Founder Eric Eisenman, DVM, MPVM, and SLC’s Darwin Initiative Nepal Program Manager, Shailendra Thakali, PhD, from Mountain Spirit. We were joined by leaders of the local municipalities, local ACAP Snow Leopard Conservation Committee, local livestock department representatives on the collaborative panel and an excellent turn out of herders, both men and women.

Our objectives for the workshops were to primarily address conflict between herders and snow leopards by discussing best practices for keeping both livestock and predators safe. We reviewed the techniques already in practice, including Foxlights, traditional corral improvements, adjusting herding practices to avoid possible high-risk situations, such as when valuable yak and calves are less protected in high pastures closer to roaming snow leopards. We covered a range of topics, including introducing One Health concepts (the interdependence of human health and animal health), and discussed parallels in this concept to Tibetan Buddhism beliefs, with one of the main aims of the workshop was to reduce the risk of transmitting diseases between people, domestic animals, and wildlife.

We discussed livestock health and mortality concerns with herders, comparing results to the pre-workshop assessment survey results our partners had gathered, reinforcing vaccination and treatment options available to them through their local municipality’s livestock department representatives. We also discussed humane treatment of livestock through improved husbandry and care to ensure they have the knowledge to meet their animal’s basic welfare needs.

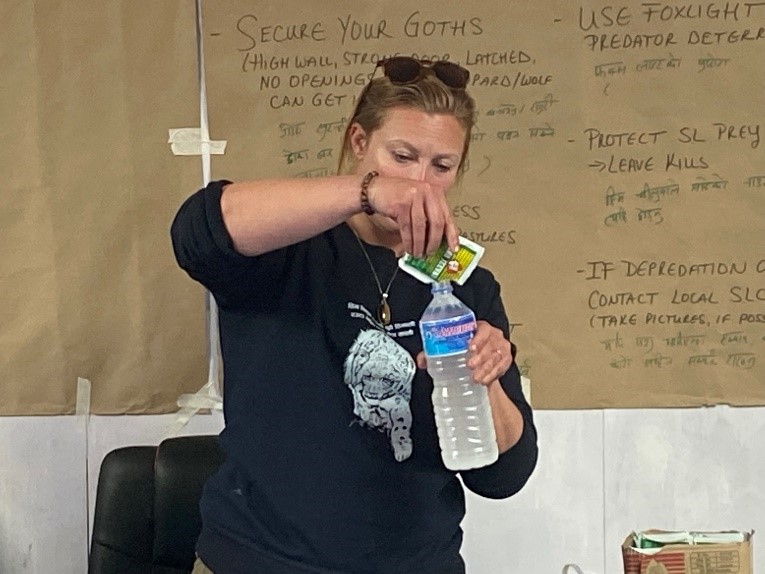

The veterinary team presented two demonstrations to train herders on supportive care for their animals, including wound cleaning and bandaging for minor (non-lethal) attacks and the use of oral rehydration salts to provide rehydration support for gastrointestinal issues. The workshops included visits to corrals and discussions on improvements to prevent possible attacks on livestock.

We hope the workshops will be helpful to the communities in promoting better health and conservation practices that benefit both people and animals. Read more about our collaborative One Health pilot program in Nepal.

When we thanked the families for their compassion following the mass depredation incidents last year, the family that suffered the losses responded that as Tibetan Buddhists, it is in their nature to be tolerant of the snow leopards and other wildlife sharing their home. It is not the nature of most herders living in these communities to intentionally harm sentient beings. However, the hard pressures of this difficult life and living in such challenging remote landscapes are reflected in the tense responses from other less tolerant herders and threaten the future of snow leopards in this region. There is yet much work to be done to address ongoing conservation and environmental challenges. Ultimately, SLC aspires to ensure that herders and livestock can live more peacefully with snow leopards and build lasting conservation measures, which requires many steps and can take many years.

One day’s walk away in Chakyu, in a freshly built government building overlooking the Nar & Phu Valleys, our team met with Narpa Bhumi Rural Municipality Vice Chair and leaders to discuss the workshops and future collaborations as we wrapped up four years of working together under the Darwin Initiative.

As I looked around the room, my eye caught the newly assembled Narpa Bhumi Rural Municipality crest which includes, under the archway of a Buddhist gompa, a snow leopard, blue sheep, yak, trekkers, Himalayan vulture, and yarsagompa (highly valued caterpillar fungus); indicative of pride in their local heritage, wildlife, and unique offerings to the broader global community. Our collective accomplishments working together the last several years has led to a sound relationship with the communities and municipality where conservation for the benefit of people, snow leopards, and other wildlife is prioritized.

Off the beaten path of the main tourist route in Annapurna, as ecotourism continues to rebound, I hope that curious and adventurous trekkers will be willing to take an extra three-day trek on the path less known and visit the incredible Nar & Phu Valleys, where ancient traditions, vibrant culture, and wildlife stronghold still flourishes.

As I take my next step toward the top of Kang La Pass, I fall into waist deep snow on the edge of the sheer cliffside. I look for my next move and take a giant step back up onto what faintly resembles a trail. I am almost to the summit, about 50 m from the top where the rest of our eager team awaits me. I balance on 4 feet of packed snow, cat walking across every step very gingerly. I am relieved to be greeted by Tabil, our head Sherpa, kindly offering to help me with my pack over the last, perhaps most formidable section. As I make it to the top of Kang La Pass, I am stunned by the incredible views of Annapurna I and II and delighted to celebrate with my team our completion of this arduous part of the journey.

Sitting under the prayer flags as they blow in the wind, I attach two additional Tibetan kata scarves I had received from the Nar and Phu communities as a gracious gift after the workshops. I do this to honor the snow leopards that I have had the privilege to know personally and those whom I do not know but promise to protect. I peer out over this sacred, magnificent landscape and pause to reflect on the journey and reasons we are here.

I feel overwhelmingly encouraged by the spirit and dedication of these incredibly resilient communities sharing their home with snow leopards, for all the hardship they continue to face living in the rapidly changing high mountain ecosystem, and for their willingness to accept our intentions to help ensure both people and animals can coexist and thrive. Thank you for inviting us into your communities and into your homes. You will forever have a place in my heart. Namaste.

Photo – Suzi Eszterhas

This One Health Veterinary Project was initiated under the umbrella of the Darwin Initiative Project (2019-2022) with three overarching outcomes:

-

Strengthened local government capacities for snow leopard conservation

-

Strengthened local community capacity for conservation of snow leopards, prey, and habitats

-

Strengthened local incentives for conservation

Many thanks to International Veterinary Outreach, Mountain Spirit, San Francisco Zoo & Gardens, and Darwin Initiative, for making this project possible through technical collaboration and financial support.

Thank you to the Nar and Phu communities, Narpa Bhumi Rural Municipality and Nar Phu Village Leaders, Annapurna Conservation Area Project Officials, Community Conservation Committee and Snow Leopard Conservation Committee Members, and to our team at Nature-Treks for assisting us and ensuring our safe journey along the way.

Please stay tuned for more updates on SLC’s recent conservation initiatives in Nepal. Your support is vital to help us continue our work, please consider making a contribution today. THANK YOU!

All photos courtesy of Ashleigh Lutz-Nelson unless otherwise indicated.