Biology

+ Where do snow leopards live?

Snow leopards are found in the mountains of Central, South, and East Asia at elevations 1,600 to 19,000 feet (500 – 5,800 meters). Their range includes the Himalayan mountains of Nepal, India, and Bhutan; Pakistan’s Karakorum and Hindu Kush; the high mountain ranges of Afghanistan, Mongolia, the People’s Republic of China, Russia and the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Snow leopard habitat is rugged and remote. These alpine big cats can even be found at the base of earth’s highest mountain, Mt. Everest, also called Sagarmatha (Nepali), Chomolungma (Tibetan), and Mt. Qomolangma (China).

Within their mountain habitat, snow leopards like high, steep, craggy and rocky places where there are few plants, places that scientists call the alpine and subalpine zones. Snow leopards live in the alpine zone in the warmer, summer months of the year. They come down into the subalpine zone in the colder, winter months following the animals that they hunt for food – the bharal or the ibex, that come down to lower elevations in search of winter grazing.

+ What do snow leopards look like?

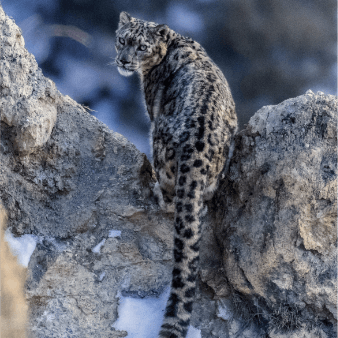

Snow leopards are the smallest of the big cats. From their nose to the base of their tail, they measure about 39-51 inches (100-130 cm). Their tail, which is the longest of any felid when compared to their body size, measures 32-40 inches (80-100 cm). It acts as a rudder as they run up and down steep rocky slopes and leap from rock to rock. Snow leopards weigh between 55 and 115 pounds (25-52 kg). As far as their proportions, they resemble a cheetah in that they have long hind limbs, which gives them a longer stride and faster running speeds. (Photo by Marianne Hale)

The snow leopard’s large paws, which act like snowshoes, measure about 4 inches long by 3 inches wide (10 x 8 cm). Snow leopards have the longest and thickest fur of any of the big cats which helps to keep them warm during the brutally cold winters, and they use their long tails to wrap around themselves like a muffler. Their fur color varies from white to cream to pale yellow or gray, sprinkled with rosettes (spots) of charcoal-grey to black. Each snow leopard has its own distinctive marking pattern. The snow leopard’s beautiful coat gives it the advantage of camouflage while hunting by being able to easily blend in with the rocks and snow. (Photo by Tashi R. Ghale)

+ How do snow leopards' physical traits help them survive in their habitat?

Snow leopards are remarkably adapted for life in mountainous regions. With their dense fur and long tail, which can wrap around their body or function as a mat for their paws to rest on, they stay warm in their cold environment. The color and broken pattern of their coats blend in perfectly with the environment, enabling them to stealthily approach prey. With a long tail providing balance as the cat navigates the steep, rocky terrain, short forelimbs, and longer hind limbs providing power, large paws providing surface area, they are adept at navigating through snow, up and down steep slopes, and across chasms. (Photo by Tashi R. Ghale)

Through a combination of unique skull features and blood characteristics, snow leopards have also adapted to the low-oxygen environments found at high elevation. Their skull has a broader and more vaulted structure with an enlarged nasal cavity and wider nasal aperture. This, combined with a high concentration of small red blood cells, allows them to maximize oxygen intake, efficiently warm and humidify inhaled air, and extract as much oxygen as possible from each breath. These physical characteristics collectively enable snow leopards to thrive in their challenging habitats. (Photo by Vikram Singh)

+ What do snow leopards eat?

Snow leopards are vital to the ecosystems of Asia’s high mountains. As apex predators, they maintain balance by hunting a variety of animals, from large prey like blue sheep and ibex to smaller creatures such as marmots and birds. Their hunting habits help control populations of grazing animals, indirectly preserving the health of alpine meadows. These meadows are crucial for wildlife, livestock, and local communities. The well-being of snow leopard populations often reflects the overall health of their mountain habitats.

When snow leopards thrive, it usually indicates a balanced ecosystem. Their presence affects everything from soil quality to plant life, demonstrating the interconnectedness of mountain ecosystems. As such, snow leopards are not just beautiful and powerful predators, but also key indicators of environmental health in their rugged, high-altitude homes.

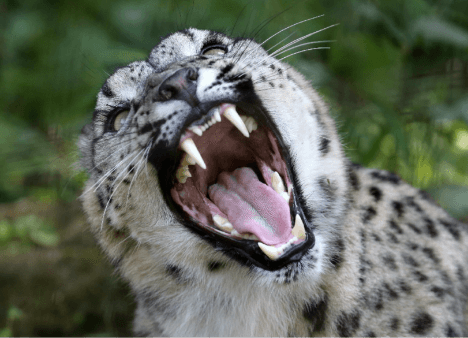

+ What sounds does a snow leopard make?

Snow leopards have unique vocal characteristics that set them apart from other big cats. Unlike lions or tigers, they cannot roar due to the absence of a specific ligament in their larynx. However, they have a diverse range of vocalizations including: prusten (a breathy, puffing sound also known as chuffing), hissing, growling, screaming, yowling, and mewing.

During breeding season, snow leopards produce a distinctive call (yowl) that echoes through their mountainous habitat. This vocalization is loud enough to carry across valleys and reverberate off cliff faces, serving as an important communication tool in their vast, remote environment.

+ How many cubs are in a snow leopard litter?

Female snow leopards usually give birth to two or three cubs with a rare occurrence of four or five in a litter. The mating season is January through March, with births occurring from April to June, following a 90 to 105-day gestation period. The cubs will generally stay with their mother for 18 months up to two years. Although generally solitary, snow leopards come together for breeding. Finding mates in their rugged terrain is difficult, so they rely on various communication methods. (Photo by Suzi Eszterhas)

In addition to vocalizations, they use a range of scent-marking behaviors including scraping, claw raking, cheek rubbing, and urine spraying to signal their presence and readiness to mate. These behaviors help these elusive cats locate each other across vast, rocky landscapes during the breeding season, ensuring the continuation of their species in one of the world’s most demanding environments. (Photo by Suzi Eszterhas)

+ How fast can a snow leopard run?

Snow leopards are capable of running very fast for short distances. However, the ability to run fast is not a particular adaptation of this big cat. The fastest cat, the cheetah, lives in open habitat where it is difficult to sneak up on prey. The cheetah instead uses speed to catch its dinner. Snow leopards live in craggy, mountainous areas, and they usually have to ambush their prey at short distances. Along with their superb camouflage, the ability to leap, bound and pounce have become this cat’s adaptations for hunting. Snow leopards have been known to leap as much as 30 feet (9.1 meters). In both running and leaping, the snow leopard is highly dependent on its tail for balance, and it is a tail unmatched by any other cat. (Photo by Gero Heine)

+ How long do snow leopards live?

In human care settings, snow leopards have been known to live to 21 years. Their lives in the wild are much harder and are consequently much shorter. The oldest adult in the wild was recorded to have lived 11 years, however, there is a lack of scientific data to know for sure what is the average lifespan of a wild snow leopard.

Conservation Facts

+ How many snow leopards are there in the wild?

The exact number of snow leopards in the wild remains uncertain, with estimates varying among different organizations and time periods. As of the last global assessment in 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) suggested there are between 2,710 and 3,386 mature individual snow leopards in Central Asia, with a decreasing population trend. In 2017, Snow leopards were officially listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Vulnerable. Snow leopards were previously listed as Endangered (IUCN, 1986-2008). Earlier estimates from other sources ranged from 4,000 to 7,500 individuals. Approximately 60% of snow leopards are believed to live in China.

The rough estimates are based on limited surveys because, as of 2021, only 23% of the snow leopards’ range had been explored, demonstrating huge gaps in knowledge of the species. Accurate counting is challenging due to the cats’ elusive nature and the difficult terrain they inhabit. (Photo by Tashi R. Ghale)

Population numbers may have decreased in some areas affected by conflict, while potentially increasing in regions with stronger protection measures. Recent technologies such as DNA analysis and camera traps are improving our ability to count these cats more accurately.

In 2017, the Global Snow Leopard Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP) initiated a protocol for a rangewide census using a standard methodology called P.A.W.S. (Population Assessment of the World’s Snow Leopards) to produce a robust estimate of the threatened cat’s population status within the next five years.

+ What threats do snow leopards face?

Lack of awareness of its value to the environment and to the local communities as a cultural and spiritual icon. Conflict with people because of depredation by snow leopards on livestock. This can result in the herder resorting to retaliatory killing of the snow leopard. As communities grow, so do their flocks and herds. The resultant overgrazing by large domestic herds damages the fragile mountain grasslands, leaving less food for the wild sheep and goats that are the snow leopard’s main prey. With less food for the wild sheep and goats, there will be fewer of these animals for the snow leopard. This leaves the snow leopard with little choice but to prey on the domestic livestock for their own survival.

Loss of and disruption of its habitat. Expanding human populations and their large livestock herds are encroaching on snow leopard habitat, displacing the snow leopard’s natural prey species.

Habitat fragmentation due to Infrastructure development such as the building of roads and rail lines, dams for harnessing hydroelectric power, and mining for gold, semi-precious stones, and minerals as well as natural resources like oil and natural gas. Also, fences and barriers are being built along international borders blocking movement corridors.

Reduction in wild prey due to illegal or poorly managed trophy-hunting programs and competition for grazing land with domestic livestock.

Illegal poaching. The bones, skin, and organs of snow leopards are used in Asian medicine when tigers are not possible to find.

Secondary or “by-catch” snaring and poisoning that is meant for other species.

Feral dog attacks have become an increasingly significant threat to snow leopards, as packs of free-roaming dogs not only compete for prey but also directly confront snow leopards, often attempting to steal their kills. This conflict can lead to injuries or fatalities, as well as the potential for disease transmission, such as rabies. Feral dogs may also carry canine distemper virus, which is fatal to big cat species.

Disease carried by domestic and other wild animals transmitted either through direct contact or parasitic infestations. There have been reports of diseases in wild snow leopards such as feline leukemia, tuberculosis, and anthrax, among others.

Military conflicts within the snow leopard’s range can have an effect on population numbers. Climate change will have extreme effects on the biodiversity of our planet because of changes in habitat. Please see question “How are snow leopards impacted by climate change?” for full description. Small population size leaves snow leopards vulnerable to extinction through reduced genetic viability.

+ How are snow leopards impacted by climate change?

With climatic warming, the permafrost layer that lies beneath most of the snow leopard’s range will warm. This warming will likely lower the water table, leading to a transformation of lush meadows into less-productive grasslands. Additionally, springs, streams, and ponds are expected to diminish and the tree line is also projected to advance to higher elevations.

All these habitat changes will result in smaller populations of the wild prey species the snow leopard depends on for food. (Photo by Steve Winter)

Of equal concern, these changes will lead to fragmentation of the entire habitat. This fragmentation will have a deleterious effect on the species as a whole by isolating individual snow leopards from one another, reducing the genetic diversity that maintains the health of the species. Agro-pastoralists will be forced to move crops and livestock into higher elevations, further isolating the cats.

In addition to disruption of the habitat, weather extremes are also expected with the changing climate, including droughts, extremely heavy, late, or early snowfalls, and partial melting and freezing of snow; all of which could result in high mortality of prey species and act as serious deterrents to successful mating and cub rearing. (Photo by Tashi R. Ghale)

+ What is the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP)?

The Global Snow Leopard & Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP) is an unprecedented alliance of all snow leopard range countries, non-governmental organizations, multilateral institutions, scientists and local communities, united by one goal: saving the snow leopard and its mountain ecosystems.

GSLEP seeks to address high-mountain development issues using the conservation of the charismatic and endangered snow leopard as a flagship. This iconic and culturally treasured great cat is a good indicator species as it quickly reacts to habitat disturbance and its successful conservation requires sustainable long term systemic solutions to the threats impacting the quality of habitats.

Saving the snow leopard will also save the world’s largest watershed, or water tower, that provides fresh water to nearly 2 billion people.

The snow leopard range countries agreed, with support from interested organizations, to work together to identify and secure at least 20 snow leopard landscapes across the cat’s range by 2020. By 2024, 24 sites had been identified, representing 28% of the snow leopard range.

+ Are there laws against killing snow leopards?

Since 1975, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) has listed snow leopards as Appendix I, banning the commercial international trade of snow leopard or their body parts. Hunting and trade has also been banned in all 12 range countries. However, snow leopard skins and body parts can still be found for sale in some of the snow leopard range countries.

The cats are protected by law, but it is almost impossible to enforce the laws in the snow leopard’s remote mountain habitat.

According to TRAFFIC International, experts estimate that 221-450 snow leopards have been poached annually since 2008.

The penalty for harming a snow leopard varies by country, from fines to imprisonment (or both).

+ Is Reintroduction an Option?

The Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Species Survival Plan (SSP) for Snow Leopards was initiated in 1981, and the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria established the European Endangered Species Program (EEP) for Snow Leopards in 1985. Under these regional ex situ conservation programs for snow leopards, accredited zoos cooperate to manage responsible breeding of individual snow leopards as a single population living within the zoological facilities. These programs will ensure that snow leopards do not become extinct and support educational awareness, research and field conservation efforts. There are currently no reintroduction plans for snow leopards. (Photo by Suzi Eszterhas)

+ What education is needed to study snow leopards?

To study snow leopards in the wild a Master’s degree in zoology, animal behavior, or wildlife management is typically needed. Experience either as a volunteer or an intern with field-based conservation groups is very helpful, allowing you to become familiar with the habitat, the techniques, and the human environment.

To work with snow leopards in human care, most entry-level zookeeper positions require a four-year degree in fields like animal science, zoology, marine biology, conservation biology, wildlife management, or animal behavior. Advanced positions in curatorial, research, and conservation often require advanced degrees and years of practical experience. Many zoological organizations offer internships for hands-on training.

Habitat & Survival

Snow Leopard Range

Snow leopards inhabit high-altitude Asian mountains, crucial “water towers” providing one-third of the Earth’s population with fresh water. As apex predators, they rely on healthy mountain prey populations and vast landscapes. These ecosystems, shared with pastoral communities, are vital for the species’ survival and water security for millions of people. Preserving this fragile environment is critical, especially as climate change and human activities pose increasing threats.

Snow leopards live in 12 countries in Central, South, and East Asia, and due to their remote habitat and elusive nature, accurate population counts remain challenging. In collaboration with the Global Snow Leopard Ecosystem Protection Program, snow leopard range countries are more accurately estimating the population using systematic criteria known as the Population Assessment of the World’s Snow Leopards (P.A.W.S.). P.A.W.S uses a combination of traditional sign surveys, camera trapping, and genetic sampling to achieve more precise snow leopard population estimates.

Top Threats to Snow Leopards

Retributive killing

ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE

Lack of awareness

Climate change

Habitat FRAGMENTATION

PrEy depletion

Zoonotic diseases

Habitat degradation

UNSUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Other High Mountain Species

Snow leopards share their habitat with many other species. Some are prey, some are competitors, and some inhabit a niche independent of snow leopards. All are necessary for a healthy ecosystem.

BLUE SHEEP

Blue sheep (Bharal) are found primarily in southern Asia (Pakistan, Nepal, India, China, and Bhutan).

They are not sheep and are not blue, they are goats that may have a slight blue sheen. Bharal are killed for trophies and for meat and are outcompeted for grazing sites by domestic herds.

Himalayan Wolf

The Himalayan wolf is found at high altitude in the Himalayas and the high Tibetan Plateau.

These wolves are social, usually living in groups of six or eight members. Humans are the primary threat to Himalayan wolves. (Photo by Tashi R. Ghale)

Pallas’s Cat

Also known as Manul, these small cats (4-11 lbs (2-5 kg)), believed to be the oldest living cat species, live throughout Asia and the Middle East, preferring uplands, hilly areas, and steppes with rocky outcrops.

They live at elevations 1,400 – 18,000 feet (450 – 5,593 meters) and ambush their prey, mainly pika, rather than chasing it.

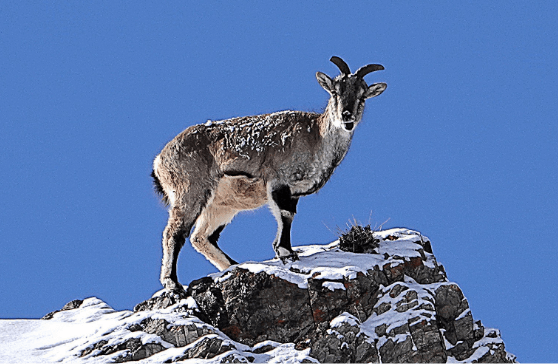

Ibex

Ibex are wild goats adapted to rugged terrain, rocky habitats, and extreme climates. Living in distinct male and female herds, they inhabit harsh climates at

elevations up to 11,000 feet (3,352 m).

Their diet has little nutritional value so much of the day is spent finding adequate food.

Marmot

Marmots are widespread small, burrow-living mammals. They are social and live in colonies composed of multiple families. They hibernate during the cold months. Their burrows help to increase soil health by aerating it. Abandoned dens are used

by Pallas’s cats. They are important prey for snow leopards, especially cubs.

Lammergeier

The Lammergeier (Bearded Vulture) is a large eaglelike vulture, frequently over 40 inches (1 meter) long, with a wingspread of nearly 10 feet (3 meters).

It prefers nesting on ledges or cliffs. Feeding on carrion, it often drops bones from a few hundred feet onto rocks below

to retrieve the bone marrow once broken. (Photo by Tashi R. Ghale)